Get the repository pattern right

The well-known patterns, repository and unit of work patterns lie at the heart of the persistence layer. A repository usually provides CRUD functions on a database entity. In order not to repeat the same tasks across all entities, a generic repository comes in the picture.

Generic Repository

public interface IRepository<T, I> where T : IEntity where I : struct

{

Task<T> GetByIdAsync(I id);

IPagedList<T> GetPagedListAsync(PageInfo pageInfo);

Task AddAsync(T entity);

void Delete(T entity);

}

If it is a common function to be shared by all entities, the generic repository is the centralised place to put it. The generic repository takes any classes which implement IEntity where Id property is defined. If you use Entity Framework, this is essential. The Id can be a type of int or GUID depending on your scenario. Thus, I is a generic type for Id.

Repository class is an implementation of IRepository. A database context gets injected through the constructor, which is likely to be Entity Framework DbContext. What the repository does is to handle DbSet of an entity for basic CRUD actions.

public class Repository<T, I> : IRepository<T, I> where T : Entity where I : struct

{

private readonly AdserveContext context;

public Repository(AdserveContext context)

{

this.context = context;

}

public async Task<T> GetByIdAsync(I id)

{

var entity = await context.Set<T>().FindAsync(id);

if(entity == null) throw new EntityNotFoundException(typeof(T).Name, id);

return entity;

}

public async Task AddAsync(T entity) => await context.Set<T>().AddAsync(entity);

public async IPagedList<T> GetPagedListAsync(PageInfo pageInfo)

{

var page = pageInfo ?? PageInfo.UseDefault();

return await context.Set<T>().ToPagedListAsync(page.Number, page.Size);

}

public void Delete(T entity) => context.Set<T>().Remove(entity);

}

Domain repository

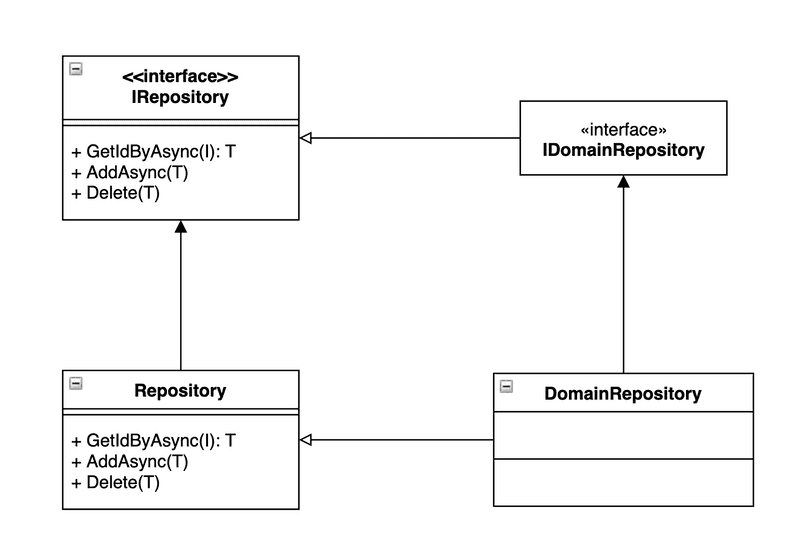

Domain repository is the one you will use in your code. Looking at the inheritance hierarchy, it implements its own interface and inherits the generic repository.

Having its own interface IDomainRepository allows to extend its function further than what the generic repository offers. You can declare more functions there which should be specific to the repository.

The diagram above does not define any domain-specific function; we call it a dumb repository. It is because the generic implementation inherited from Repository class is just good enough.

Below is a sample code to retrieve a paged list of sites. Unit of work is what you need.

[ApiController]

[Route("api/[controller]")]

public class SiteController : ControllerBase

{

private readonly IUnitOfWork uow;

public SiteController(ILogger<StationController> logger, IUnitOfWork unitOfWork)

{

uow = unitOfWork;

}

[HttpGet("all")]

public async Task<IActionResult> GetAll()

{

var sites = await uow.Sites.GetPagedListAsync();

if (sites.Count == 0) return NotFound();

return Ok(sites);

}

}

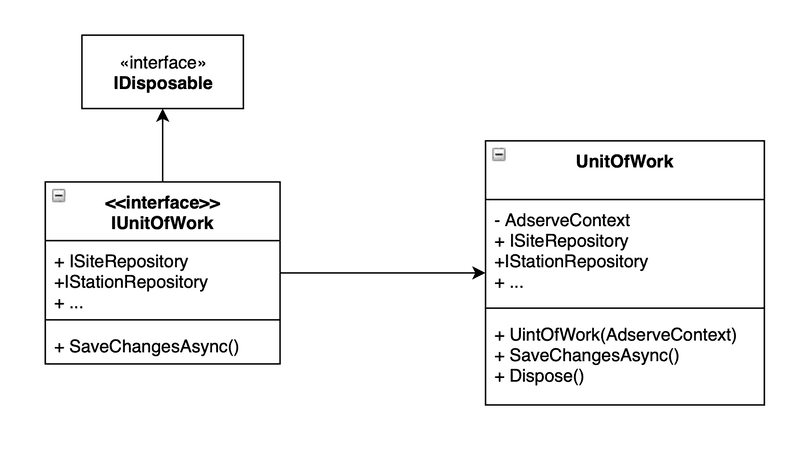

Unit of work

One of the common mistakes of using the repository pattern is that people implement a save method inside the repository while the repository should work as a collection. Adding an entity, modifying it and removing it are the responsibility of the collection, but it doesn't save itself. Unit of work is a container of all repositories and instantiates them in it. Thus, a repository is obtained via the unit of work, and it saves all changes across multiple repositories in a transaction.

Unit of work hides DbContext as developers are not expected to directly use it. Note that the constructor expects a DbContext. It is important to have an instance of the context before creating an instance of the unit of work.

The unit of work wraps the context and control the repositories as below.

public class UnitOfWork : IUnitOfWork

{

private readonly ApplicationContext context;

public ISiteRepository Sites { get; }

public ICampaignRepository Campaigns { get; }

public UnitOfWork(ApplicationContext context)

{

this.context = context;

Sites = new SiteRepository(context);

Campaigns = new CampaignRepository(context);

}

public Task<int> SaveChangesAsync()

{

return context.SaveChangesAsync();

}

public void Dispose()

{

context?.Dispose();

}

}

Following code is extracted from a unit test. Don’t forget to call SaveChangesAsync() in the end of the process unless you want to lose the changes.

using var uow = new UnitOfWork(AdserveContextFactory.Create());

var entity = await uow.Stations.GetByIdAsync(stationId);

uow.Stations.Delete(entity);

await uow.SaveChangesAsync();

Aggregate root

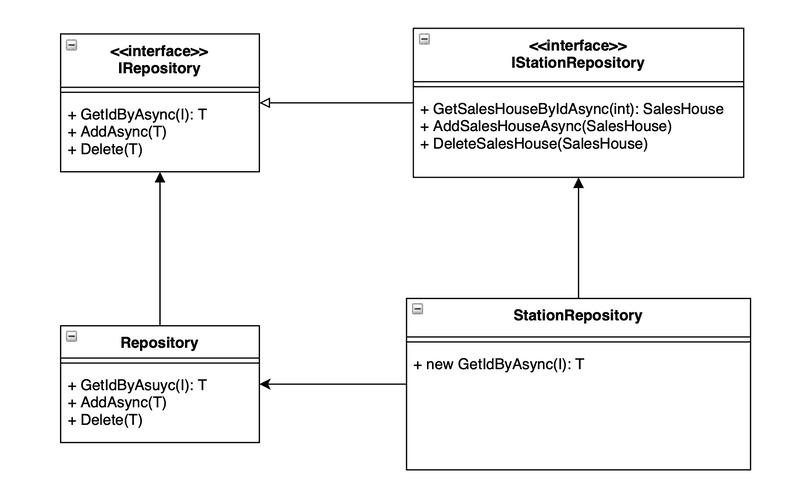

Think the number of database tables. If each table happens to be an individual repository, the unit of work is bombarded with repositories. It also doesn't look logical to work on Order and LineItem, for example, with OrderRepository and LineItemRepository respectively. LineItem can be accessed and managed through the Order.

Aggregate root encapsulates a primary entity with child entities and is exposed to the unit of work. It not only reduces the number of repository also, makes functions more complete with associated entities.

A diagram above shows an aggregate repository for Station that encapsulates SalesHouse. IStationRepository is not a dumb repository here; it defines some additional functions on behalf of SalesHouse entity.

While StationRepository still inherits the generic repository capabilities, there is a case that it needs to override a generic implementation.

Use new keyword to hide the default behaviour.

// StationRepository.cs

public new async Task<Station> GetByIdAsync(int id)

{

var station = await context.Stations

.Include(s => s.SalesHouse)

.SingleOrDefaultAsync(s => s.Id == id);

if (station == null) throw new EntityNotFoundException("Station", id);

return station;

}

The code above hides the default behaviour from Repository.cs below. For aggregate root, it is likely to be fetched with its child objects so it returns an object graph.

// Repository.cs

public async Task<T> GetByIdAsync(I id)

{

var entity = await context.Set<T>().FindAsync(id);

if(entity == null) throw new EntityNotFoundException(typeof(T).Name, id);

return entity;

}